Sometime between 2000 and 2004, a remarkable example of grassroots, creative non-violent resistance to military occupation took root in villages of the West Bank. So much violence and upheaval was taking place in the region at the same time that this phenomenon may have gone unnoticed.

Sometime between 2000 and 2004, a remarkable example of grassroots, creative non-violent resistance to military occupation took root in villages of the West Bank. So much violence and upheaval was taking place in the region at the same time that this phenomenon may have gone unnoticed.

Thirty-plus years of Israeli military occupation (punctuated by intensified land grabs and settlement construction), as well as dashed hopes for a just peace, set the stage for this phase of Palestinian resistance. But, the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back was, ironically, Israel’s creation of a wall to insulate its population from Palestinians. Instead, the construction of the Separation Barrier (as deemed by its designers) broke the fear barrier once and for all for many of the rural residents lying in its wake. (This occurred, incidentally, just as cracks in the wall of fear were about to undermine regimes all across the region).

Bil’in lies near the “green line” separating Israel proper from the West Bank. Israel’s “Separation Barrier” divided the town from its olive groves and sparked a resistance movement which has made international headlines and is brought home by Burnal and David’s film.

Sometime in 2008, Sandra told me to watch these amazing YouTube videos of protests against the wall in a little village in the district of Ramallah called Bil’in. Every Friday, villagers– women, men, young, old– and, over time, Israeli and international supporters, would march up to the barrier to face off with heavily armed and armored soldiers. The army would respond with gas, rubber bullets, and live ammunition. Defenseless civilians (alright, some of the boys through rocks) were gassed, wounded, and shot dead at point blank range.

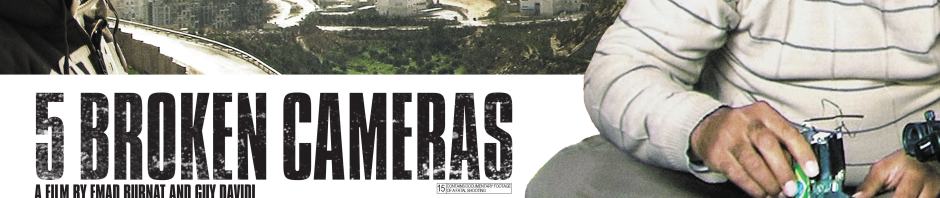

I did not know at the time that these videos were produced by the village’s de facto chronicler Bil’in native Emad Bunat whose home movies turned into an extraordinary documentary. Burnat and Israeli director Guy David produced the extraordinary documentary Five Broken Cameras (2011). A theatrical trailer is available at the website of distributor Kino Lorber. I just saw it streaming on Hulu Plus. If you aren’t a subscriber, you can sign up for a free one-week trial. It is well worth it. A Facebook page has more details about the film.

My mentor Tony Bing used to say that you cannot understand Palestinians, especially the rural population, unless you understand their attachment to the land. He called “continuity of presence on the land” the single most important Palestinian truth. Of course, Palestinians know this intuitively and I will never forget seeing Palestinian geographer Kamal Abdul Fattah tasting the soil as he examined the remnants of a village deserted and destroyed in 1948 as we stopped on a trip to the Galillee.

Filmmaker Emad Burnat with his son Gibreel on the lands of their village Bil’in with the Separation Barrier and the Israeli settlement of Modi’in Illit in the background. Photo by Rina Castelnuovo for The New York Times.

This passion for the land is made tangible by Burnat’s first person narrative (subtitled for English-language audiences). He and his neighbors had no desire to be caught up in politics and confrontation. But when Israeli settlers from the settlement of Modi’in Illit, which casts a larger and larger shadow over the village, burned a grove of olive trees, the villagers’ anger boiled over. As the backhoes scored the land to build the fence, Burnal decries “the wounds in the land” that leave scars like those left by bullets tear gas canisters on the bodies of his compatriots.

Burnal’s elderly father musters all the energy of a parent to try to stop his son Khalid’s imprisonment.

Burnat got the first (of the title’s five) cameras to take home movies when his fourth son Gibreel was born in 2005, just as the weekly protests began. Over the next five years, Gibreel grows as do the confrontations with the military. His birthday parties are bracketed by the arrests of his uncles Riyad, Eyad, Ja’far, and Khalid (not to mention the eventual jailing of his father). His first words are matat (cartridge), jidar (wall), and jaysh (army). Burnat’s wife Soraya is increasingly frustrated by her husband’s obsessive filming and propensity to find trouble. He is wounded, saved from certain death by camera no. 3 which takes two bullets, jailed, put under house arrest, and barely escapes death when his tractor collides with the fence. Soraya cries when her husband defies doctors’ orders to film again, “What are we supposed to do? I can’t take it! I am tired!” Burnat’s view is family focused and unflinching. When brother Khalid is arrested, Burnat films his elderly parents clawing at an armored jeep to prevent the soldiers’ retreat with their son.

Adeeb and “Phil” lead a demonstration in Bil’in. They march right up to a line of heavily armed and armored Israeli soldiers with nothing but deep attachment to their land and a spirited resolve to protect it any cost.

This is a film about family and friendship. Burnat’s two closest friends, Adeeb Abu Rahme and the larger than life Bassem Abu Rahme (Adeeb’s cousin), exhibit rare bravery as they use their bodies, voices, and, most importantly, imaginations, to challenge everything the Israeli military launches at them. Bassem is known as “Phil” for fil, Arabic for “elephant” for his size and his circus antics that keep village children from growing up in complete despair. Together and with the aid of other villagers and solidarity activists, this motley band of citizen-resisters challenges every effort to take the land with progressively more creative responses. When Israeli settlers use a trailer to create “facts on the ground”, Bil’inis try blocking the cranes with their bodies. When that fails, they create an outpost of their own. When that is torn down, they replace it. When the second trailer is seized with activists locked inside, the villagers gather at night to construct a concrete version which is repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt.

Little victories are achieved along the way. The Israeli High Court orders the fence moved and though it takes more than five years for this to happen, it was entirely the result of the resolve and resourcefulness of “little people”, villagers and their civilian supporters. When Palestinian politicians show up to take advantage of this resilience, the villagers are ambivalent if not entirely skeptical of their intentions.

[Spoiler alert; skip to the next paragraph.] It is not always, clear, however whether the small victories are worth the devastating costs. Soraya, the filmmaker’s wife knows this (as only a mother can) from the start. But, when the playful giant Phil is finally shot dead by an Israeli soldier, even Burnat has his doubts. Gibreel, aged five and very attached to Phil, begins to ask questions that reveal the loss of innocence. “What did Phil ever do to the jaysh to be killed?”

This deeply personal account will leave the most hardened viewer shocked and inspired. Bernat’s cameras capture the loss of humanity among Israeli settlers and soldiers who fire directly into crowds of unarmed civilians; who are unmoved by pleading mothers as they arrest and imprison children; and who volley enough gas to engulf an entire village.

Bernat concludes by reflecting on his broken community and his broken body. In the end, he says, resistance and healing are one and the same. That his community has maintained its resilience and humanity in the face of such odds is a testament to the power of the human spirit and of non-violent resistance.

The film brings this message home up close and personal. For those of us watching from afar, the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement is a means for engagement in the same vein albeit from the comfort of worlds where our cameras are safe from bullets and batons.

Interesting post.I honestly don’t know all that much about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and especially why so many Americans side with Israel. I think your post shed a little more light on the issue for me, and helped me to better understand the suffering faced by the Palestinian people.

Rolo,

Apologies for the late reply. Let me know if you have specific questions. Given your interest in the ancient history of the region, I trust you know more than you are letting on.

No worries about the late reply. Haha, unfortunately I have to disappoint you. I actually don’t know much about the conflict at all, like what’s Hamas or Hezbollah? I feel like the entire conflict is something many people like me hear about, but few understand.

It’s not as complicated as most Americans think it is. This film explains a lot in terms of the current situation on the ground.